"Artist Mengfan Bai, recently held a solo exhibition titled "蚀金" (Circular). In this show, she draws inspiration from ancient Chinese bronzeware and everyday life scenes, enlarging the corroded textures and distilling the surface symbols of these vessels to embody the passage of time and the evolution of human civilization.

Mengfan told me that the English title "Circular" was the first element she settled on—it refers not only to the shape of a circle, but also subtly suggests the idea of cycles and reincarnation. While we often perceive the passage of time as a one-way river, isn’t our reflection on history a form of circling back? The thoughts and emotions that linger most are often those tied to things long past.

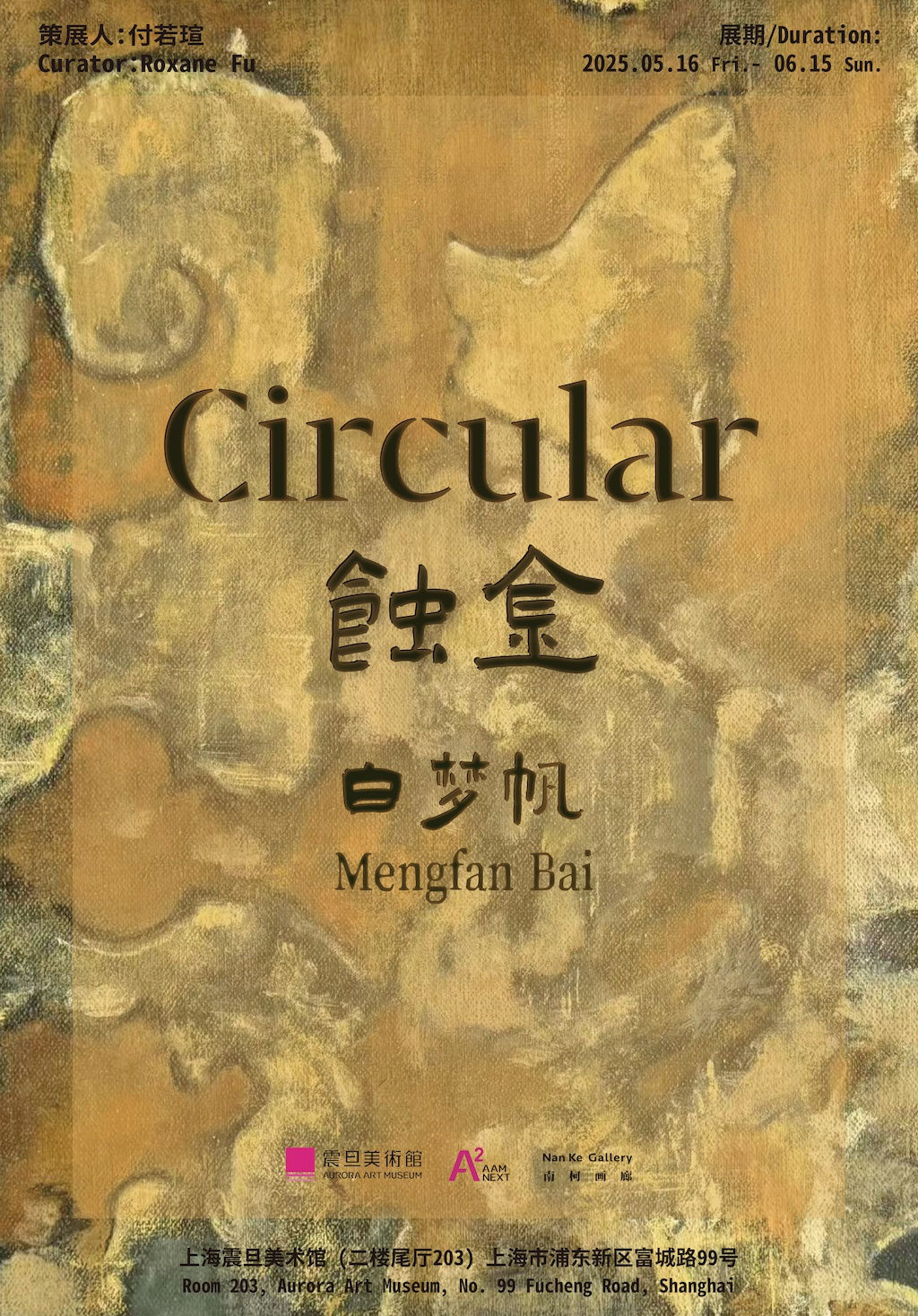

Installation view of Circular, May 16, 2025 - June 15, 2025, Aurora Art Museum, Shanghai © Courtesy of Nan Ke Gallery, Photographed by Runxin.

To me, the Chinese title “蚀金” (literally “eroded gold”) is even more evocative: the peeling of a metal surface stands as physical evidence of erosion by both time and external forces. It reveals the flow of history, creating a tension between the movement of time and the stillness of objects. At the entrance of the exhibition, two paintings of fountains face each other — in one, the water shimmers like flames; in the other, it lies still as a mirror.

The narrow white exhibition hall resembles a “tunnel of time,” echoing “蚀金”'s metaphor of temporal erosion. Each artwork on the wall feels like a historical node—landscapes that evoke emotion—illuminated one by one as visitors move through the space.

Installation view of Circular, May 16, 2025 - June 15, 2025, Aurora Art Museum, Shanghai © Courtesy of Nan Ke Gallery, Photographed by Runxin.

Perhaps the most striking part of the exhibition is an entire wall of paintings portraying ritual bronze vessels, spanning from the Shang and Zhou dynasties to later periods, arranged in historical sequence from near to far. With meticulous brushwork, Bai Mengfan captures the varying shades of rust on the bronzes’ surfaces, and even more attentively, the marks left by ancient craftsmen who carved entirely by hand. She pointed out one vessel adorned with fish-scale motifs:

"The curve here is slightly rough," she said, "because the craftsman relied solely on touch to carve it. These flaws, these traces—they fascinate me."

At the very end of the gallery hangs Bronze Birds. Two bronze sparrows perch side by side beneath the eaves of an ancient structure—the image is tender, but its truth, brutal. The scene is based on a bronze shell container titled Scene of Oath and Curse, which depicts the ritual culture of the ancient Dian Kingdom. Omitted from the frame is the vessel’s darker side: oxen being driven forward, horses slain, pigs and sheep butchered, even humans sacrificed to the heavens. Quiet intimacy and bloody ritual stand in silent opposition within a single object, together forming an eerie, surreal atmosphere.

Installation view of Circular, May 16, 2025 - June 15, 2025, Aurora Art Museum, Shanghai © Courtesy of Nan Ke Gallery, Photographed by Runxin.

To me, Bai Mengfan’s artistic expression extends far beyond her primary medium of painting. The texts and numbers she records for each work carry intentional, layered meanings. For instance, her fountain series is titled Spring Plaza (灵沼正涵春). The name refers to the actual location of the fountains—Hanchun Plaza—but after browsing through classical Chinese poetry, she unexpectedly came across a line in On Command: Admiring Flowers and Fishing by Song dynasty poet Fan Zhongyan: “Freshly washed in spring rain, the spiritual pond holds the season's essence.” She took the latter phrase—“灵沼正涵春”—and used it as the title. Similarly, works like Earth Green 2220, Turquoise 3600, and Bronze Blue 2220 begin with traditional Chinese color names, followed by numbers indicating the approximate number of years since the bronze vessel’s creation. However, as Bai Mengfan explained, she deliberately omits labels like “AD” or “BCE,” leaving only the bare numbers. This allows them to read ambiguously—as both timelines and color codes—deliberately leaving space for the viewer’s interpretation.

In past conversations, I’ve come to sense in Bai Mengfan’s practice a distant yet restrained classical Chinese aesthetic. For example, in her Tennis Court series, tennis balls are scattered across a dark blue court, but their forms are intentionally blurred, reduced to points of light. Reflecting on these works, she once said: “It reminds me of something the Ming dynasty literatus Li Rihua once wrote: ‘The finest realms in painting lie in the vague and the faint.’” (From “The Recluse's Remarks on Painting”) To her, that scene embodies a very Chinese sense of “subtle haze” and “faint desolation.”

Installation view of Circular, May 16, 2025 - June 15, 2025, Aurora Art Museum, Shanghai © Courtesy of Nan Ke Gallery, Photographed by Runxin.

The same sensibility is evident in the works featured in this solo exhibition—particularly those centered on ancient Chinese bronzeware. What Mengfan captures is not a complete or literal representation of these artifacts, but rather a magnified and refined focus on specific fragments. In doing so, she diffuses the grandeur, historical weight, and sacred solemnity typically associated with such objects. Removed from the gravity of academic study, these forms are reframed through their most immediate craftsmanship—presented instead as symbols. She navigates deftly between the dignity of history and the lightness of expression, allowing the spirit of Chinese culture to emerge subtly, flowing freely and unforced.

Mengfan’s creative process often begins with moments she captures from her daily life. She photographs scenes that catch her attention, then later transforms them onto canvas. I once asked her how this approach differs from the objectivity of photography. Now I understand: what she preserves in paint is not simply a frozen moment in time, but a trace of her emotional state—her thoughts and feelings, lingering quietly in the frame."

Installation view of Circular, May 16, 2025 - June 15, 2025, Aurora Art Museum, Shanghai © Courtesy of Nan Ke Gallery, Photographed by Runxin.

Text by 徐小喵Jessica Xu

ART TALK | Dialogue with Mengfan Bai

1.Why did you choose “copper” as the central medium for this exhibition? How is it connected to your previous focus on the theme of “metal currency”?

In fact, choosing copper wasn’t a deliberate decision—it felt more like a natural return. Copper is a native metal, meaning it exists in metallic form in nature. Thousands of years ago, humans could use it directly without the need for complex refining techniques. For me, this “immediacy” is not only physical but also conceptual. Copper is a metal we can quite literally reach across time to touch—its presence spans nearly the entirety of human civilization.

In my past work, I’ve been interested in the history, systems, and symbolism of metallic currency—things like the gold standard or the colonial trajectories of silver coins. But copper is a little different. Within monetary systems, it often occupies a marginal position—not particularly precious, yet found everywhere. For example, in many countries before the 19th century, copper coins were used for the most ordinary, everyday transactions. Copper connected to common people, to small exchanges, to peripheral structures of society.

Copper’s history is also a story of intersecting technological and political developments. From the first hammered native copper, to the invention of smelting, to the creation of bronze as the first alloy—behind all this lies a web of stories about how resources, energy, and knowledge move and concentrate. My interest in metals has always been about how they shape our understanding of value, materiality, and permanence.

And then there’s copper’s color, which I find deeply moving. It often has a warm and complex tone—one that oxidizes and turns green over time. It’s constantly changing, which reminds me of how the value of currency, too, is always being redefined—by time, by systems, by the behavior of society.

2. In your work, “rust” serves as both a symbol of time and a source of poetic power. How do you understand the aesthetic and philosophical significance of rust?

The Italian theorist of material heritage conservation, Cesare Brandi, once wrote: “From an aesthetic point of view, patina imperceptibly lowers the tone of the material, forcing it into a more modest role embedded within the image itself.”

To me, rust is both a protective layer and a key to authenticity. It’s a surface that safeguards, but also a visual indicator of the passage of time—a trace that helps us determine whether an object is “real.” Rust records time in its own unique way. It tells history, and at the same time, constantly rewrites it.

3. In your creative process, how do you navigate the relationship between the material reality of copper and the language of painting?

When working with copper, I’m more interested in the textures it accumulates across different historical periods. In Turquoise3600, I used sand to simulate the thickness of corrosion layers. The rough edges resemble traces of copper entangled with time, while the central turquoise area is smooth, almost mineral-like in its sheen. The two surfaces are placed side by side, creating a kind of juxtaposition.

Texture34, on the other hand, depicts a more modern object—an elevator door. Unlike ancient bronzeware, it doesn’t have that same sense of weight; instead, it has a more refined, uniform surface produced by industrial processes. Yet, it still oxidizes—only now into a thin, dark brown film. In this painting, I used lighter brushwork to gradually layer the colors, letting the oxidation emerge subtly rather than emphasizing it outright. It’s a way of portraying copper’s current state, and of exploring how its texture evolves in a contemporary context.

4. Do you believe that material itself—such as copper—possesses a kind of “memory”? How does an artist activate that memory?

I do believe that material carries memory—especially something like copper, which has passed through long spans of time and diverse uses. Every piece of copper holds traces of the geography, society, and technology it once belonged to. Its patterns, its craftsmanship, even the marks of oxidation—these are all slices of time, sealed fragments of historical information.

Art, in this sense, acts as a kind of conduit. As an artist, I turn to be someone who extracts those temporal signals embedded in material, amplifies them, and transforms them into images or objects that can awaken memory and imagination in others. What you see might be a piece of copper, but what it evokes could be a texture from an era you’ve never lived through, yet somehow still feel deeply familiar.

5. Your work often weaves together grand themes of civilization with a personal perspective. What does this approach mean to you as a creative strategy?

In the past, I feel emotionally distant from connecting to bronzeware—perhaps because it’s so often wrapped in grand historical narratives. It felt distant, solemn, even a bit unapproachable. That changed when I saw some bronzes in overseas museums that weren’t encased in glass. Their exposed, rusted surfaces made me feel—perhaps for the first time—their vulnerability and material reality. And that moment sparked a question in me: What is my relationship to these things?

So for me, pulling civilizational themes back into the realm of individual experience is both a strategy and a way of drawing closer. Painting offers a slow, intimate passage—one where I can engage with the texture and temporality of these objects, and in doing so, begin to reconnect with my ancestors. In a sense, I’m transforming these seemingly remote traces of civilization into fragments that can be touched, remembered, and personally felt.

6. What kind of work do you hope to explore next?

Going forward, I want to focus more on the “invisible copper” in our lives and urban memories—those parts of the city that are wrapped up, overlooked, or hidden in plain sight. Though they’re not visually prominent, they form the foundational infrastructure of urban life and carry a quiet sense of historical presence.

Through painting, I hope to excavate these latent copper elements—not out of nostalgia, but to ask how such materials are forgotten or persist in contemporary life. It’s about returning to a more everyday, and also more delicate, layer of time.